WORLD WAR II FROM A TO Z

Click to view slideshow.

Women all over the world contributed to their country’s effort in the Second World War. Many of these women served in the armed services. To write about them all or even just those for the Allied Powers would be a very large under taking. Today I write about American women in the armed services but rest assured, the Americans were just one part.

During World War II, approximately 400,000 U.S. women served with the armed forces and more than 460 — some sources say the figure is closer to 543 — lost their lives as a result of the war, including 16 from enemy fire. However, the U.S. decided not to use women in combat because public opinion would not tolerate it. Women became officially recognized as a permanent part of the U.S. armed forces after the war, with the passing of the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act of 1948.

The Women’s Armed Services Integration Act of 1948, signed into law by President Harry Truman on June 12, 1948, gave women permanent status in the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corp.

More than 60,000 Army nurses (all military nurses were women at the time) served stateside and overseas during World War II. They were kept far from combat but 67 were captured by the Japanese in the Philippines in 1942 and were held as POWs for over two and a half years. One Army flight nurse was aboard an aircraft that was shot down behind enemy lines in Germany in 1944. She was held as a POW for four months. In 1943 Dr. Margaret Craighill became the first female doctor to become a commissioned officer in the United States Army Medical Corps.

Lt. Col. Margaret D. Craighill, M.C.

The Army established the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) in 1942. WAACs served overseas in North Africa in 1942. The WAAC, however, never accomplished its goal of making available to “the national defense the knowledge, skill, and special training of the women of the nation.” In 1942, Charity Adams (Earley) became the first African-American female commissioned officer in the WAAC. The WAAC was converted to the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) in 1943, and recognized as an official part of the regular army. I follow a blog called My Aunt the WAC. It is interesting to read a personal story of a WAC.

More than 150,000 women served as WACs during the war, and thousands were sent to the European and Pacific theaters; in 1944 WACs landed in Normandy after D-Day and served in Australia, New Guinea, and the Philippines in the Pacific. In 1945 the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion (the only all African-American, all-female battalion during World War II) worked in England and France, making them the first black female battalion to travel overseas.

Major Charity Adams Earley and battalion

The battalion was commanded by MAJ Charity Adams Earley, and was composed of 30 officers and 800 enlisted women. WWII black recruitment was limited to 10 percent for the WAAC/WAC—matching the percentage of African-Americans in the US population at the time. For the most part, Army policy reflected segregation policy. Enlisted basic training was segregated for training, living and dining. At enlisted specialists schools and officer training living quarters were segregated but training and dining were integrated. A total of 6,520 African-American women served during the war.

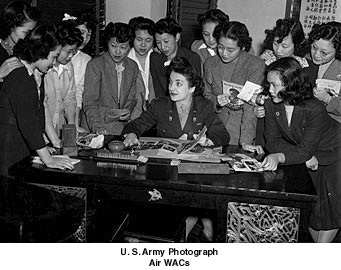

Asian-American women first entered military service during World War II. The Women’s Army Corps (WAC) recruited 50 Japanese-American and Chinese-American women and sent them to the Military Intelligence Service Language School at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, for training as military translators. Of these women, 21 were assigned to the Pacific Military Intelligence Research Section at Camp Ritchie, Maryland. There they worked with captured Japanese documents, extracting information pertaining to military plans, as well as political and economic information that impacted Japan’s ability to conduct the war. Other WAC translators were assigned jobs helping the US Army interface with our Chinese allies. In 1943, the Women’s Army Corps recruited a unit of Chinese-American women to serve with the Army Air Forces as “Air WACs.” The Army lowered the height and weight requirements for the women of this particular unit, referred to as the “Madame Chiang Kai-Shek Air WAC unit.”

The first two women to enlist in the unit were Hazel (Toy) Nakashima and Jit Wong, both of California. Air WACs served in a large variety of jobs, including aerial photo interpretation, air traffic control, and weather forecasting. Susan Ahn Cuddy became the first Asian-American woman to join the U.S. Navy in 1942.

More than 14,000 Navy nurses served stateside, overseas on hospital ships and as flight nurses during the war.

Five Navy nurses were captured by the Japanese on the island of Guam and held as POWs for five months before being exchanged. A second group of eleven Navy nurses were captured in the Philippines and held for 37 months. (During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, some Filipino-American women smuggled food and medicine to American prisoners of war (POWs) and carried information on Japanese deployments to Filipino and American forces working to sabotage the Japanese Army. The Navy also recruited women into its Navy Women’s Reserve, called Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES), starting in 1942.

Women entered the Hospital Corps in World War II as WAVES.

Before the war was over, 84,000 WAVES filled shore billets in a large variety of jobs in communications, intelligence, supply, medicine, and administration. The Navy refused to accept Japanese-American women throughout World War II. USS Higbee (DD-806), a GEARING-class destroyer, was the first warship named for a woman to take part in combat operation. Lenah S. Higbee, the ship’s namesake, was the Superintendent of the Navy Nurse Corps from 1911 until 1922.

Marine Corps Women’s Reserve

The Marine Corps created the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve in 1943. That year, the first female officer of the United States Marine Corps was commissioned; the first detachment of female marines was sent to Hawaii for duty in 1945. The first director of the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve was Mrs. Ruth Cheney Streeter from Morristown, New Jersey.

Ruth Cheney Streeter

Captain Anne Lentz was its first commissioned officer and Private Lucille McClarren its first enlisted woman; both joined in 1943. Marine women served stateside as clerks, cooks, mechanics, drivers, and in a variety of other positions. By the end of World War II, 85% of the enlisted personnel assigned to Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps were women.

Coast Guard SPARS

In 1941 the first civilian women were hired by the Coast Guard to serve in secretarial and clerical positions. In 1942 the Coast Guard established their Women’s Reserve known as the SPARs (after the motto Semper Paratus – Always Ready). YN3 Dorothy Tuttle became the first SPAR enlistee when she enlisted in the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve on 7 December 1942.

LCDR (later CAPT) Dorothy Stratton

LCDR Dorothy Stratton transferred from the Navy to serve as the director of the SPARs. The first five African-American women entered the SPARs in 1945: Olivia Hooker, D. Winifred Byrd, Julia Mosley, Yvonne Cumberbatch, and Aileen Cooke. Also in 1945, SPAR Marjorie Bell Stewart was awarded the Silver Lifesaving Medal by CAPT Dorothy Stratton, becoming the first SPAR to receive the award. SPARs were assigned stateside and served as storekeepers, clerks, photographers, pharmacist’s mates, cooks, and in numerous other jobs during World War II. More than 11,000 SPARs served during World War II.

In 1943, the US Public Health Service established the Cadet Nurse Corps which trained some 125,000 women for possible military service.

In all, 350,000 American women served in the U.S. military during World War II and 16 were killed in action. World War II also marked racial milestones for women in the military such as Carmen Contreras-Bozak, who became the first Hispanic to join the WAC, serving in Algiers under General Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Minnie Spotted-Wolf, the first Native American woman to enlist in the United States Marines.